It’s been a momentous few weeks in the world of central banking.

Persistent inflation pressures have prompted global central banks to accelerate their plans, and we now anticipate the most aggressive and synchronized global tightening cycle since the early 1980s. The key question now is not whether central banks will slam on the brakes but what might stop them?

The Bank of Canada increased interest rates by 0.5% in early June. Then, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) followed shortly thereafter mid-month with a super-sized 0.75% hike. It was the most prominent sign yet of global central banks’ markedly hawkish shift in recent weeks. Policymakers from Australia to India have stepped up the pace of monetary tightening. The European Central Bank has outlined plans for a relatively aggressive lift-off in rates starting in July, and even at the Bank of England, three members of the Monetary Policy Committee voted for a larger 50 bps increase last week, despite data showing a surprise contraction in the U.K. economy in April.

This sudden shift in the speed of interest rate increases lies behind the latest volatility in financial markets, which has, in turn, fuelled breathless commentary by the financial press about new global economic and financial crises. At such times, it pays to step back and consider the bigger picture. A couple of points are worth stressing.

"central banks are starting from an ultra-accommodative position, and that economies and inflation are running hot, it makes sense for them to front-load tightening.”

First, central banks are starting from an ultra-accommodative position, and that economies and inflation are running hot, it makes sense for them to front-load tightening. I wrote in my Q1 commentary that the priority for central banks would be to return interest rate policy to a more neutral setting as soon as possible. They need to rein in inflation, a large portion of which is out of their control while supporting economic growth and the financial markets. My expectation was - and still is - that central banks may be willing to sacrifice financial markets to keep economic growth momentum positive. The war in Ukraine has given an additional impulse to inflation, making it even more important that policymakers move from a defensive to an offensive position on inflation.

Accordingly, we should expect more hawkish moves from central banks over the next few months. This will lead to continued volatility in financial markets and hit vulnerable emerging markets like Turkey, but central banks will view this as a price that has to be paid for regaining the lead on inflation.

"it’s important to distinguish between the speed at which interest rates are increased and the level at which they’re ultimately raised.”

Second, it’s important to distinguish between the speed at which interest rates are increased and the level to which they’re ultimately raised. The extent of monetary tightening that will be required from central banks will depend on the balance between aggregate demand and each economy’s ability to supply goods and services. Remember, inflation can be distilled down to a simple imbalance between supply and demand. Central banks are powerless to affect the supply of goods and services, which has been impacted by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. They can only affect the demand for goods and services by loosening or tightening the cost of credit. The fact that most economies now seem to be running hot suggests that most central banks will - to some extent - need to bear down on demand. But central banks might also get a helping hand from improving supply-side of economies.

In particular, employment markets are still feeling the effects of the pandemic. This is manifesting itself in different ways: in the U.S., participation rates are low relative to pre-COVID norms. In the euro-zone hours worked have yet to fully recover, and in the U.K., long-term sick rates have risen, pushing workers out of the labour market. There is scope for labour supply to improve in all developed market economies as pandemic-era frictions ease and, while this won’t help the inflation picture in the very near term, it could make central banks’ lives easier over the next year or so. The uncertainty around supply-side dynamics complicates the judgement as to how far (rather than how fast) interest rates will need to rise.

“Closer to home, we think that the Bank of Canada will move to the sidelines later this year as inflation drops back and it becomes clear that a more severe downturn in housing is developing.”

Irrespective of this, the peak in interest rates will differ between countries. In the U.S., excessively strong demand means that the Fed will need to push policy rates somewhat above neutral (we’ve pencilled in the Fed Funds rate to peak at 3.75-4.00%). Closer to home, we think that the Bank of Canada will move to the sidelines later this year as inflation drops back and it becomes clear that a more severe downturn in housing is developing. We’ve pencilled in a peak in a bank rate of 3.0%.

Interest rates in the euro-zone are likely to peak at a lower level. For a start, aggregate demand isn’t as hot in the euro-zone as it is in the U.S. This is partly because pandemic-era stimulus was smaller but also because, unlike in the U.S., the euro-zone has experienced a substantial deterioration in its balance of payments as global commodity prices have surged. Moreover, neutral interest rates are probably lower in the euro-zone than in the U.S.

So, Where Do We Go from Here?

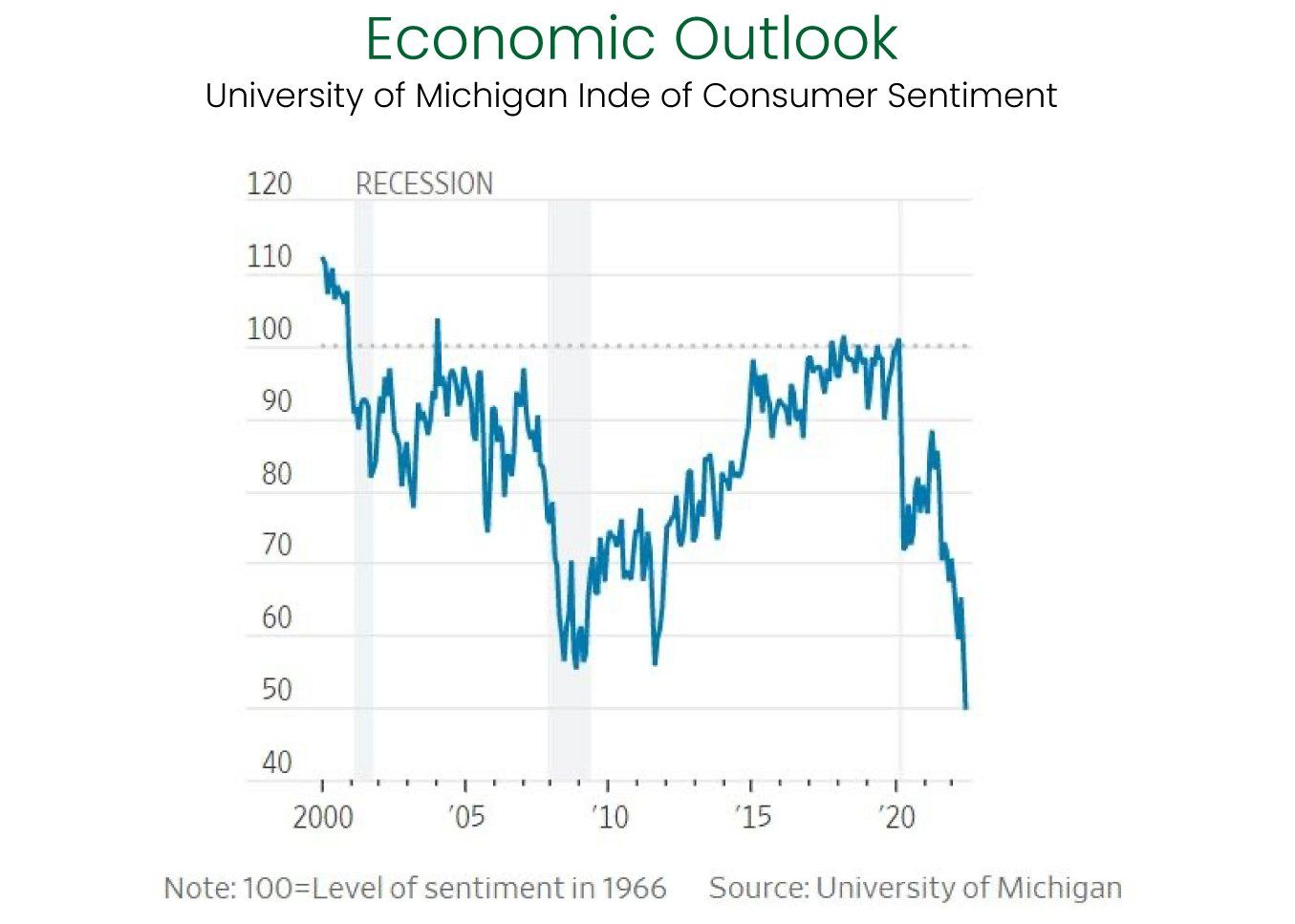

Circling back to the commentary by the financial press about new global economic and financial crises, sentiment indicators, such as the University of Michigan Index of Consumer Sentiment, are at all time lows, suggesting that consumers are anticipating a recession.

“Our review of multiple financial risk indicators suggests that recession risks are still low.”

Our review of multiple financial risk indicators suggests that recession risks are still low. Central banks’ rapid policy tightening will trigger a marked slowdown in global economic growth, which means that the risks of recession are likely to build over the coming quarters. In our opinion, suggestions that a recession is imminent or inevitable are well off target. Although we don’t expect a recession, if one does occur, we would expect that it will be a mild one.

As I noted in my last commentary, Headwinds Ahead, we expect equities to lose more ground between now and the end of the year. We think that rising “risk-free” rates will continue to weigh on equity valuations this year, in some places more so than we previously thought. We have also turned more downbeat on the economic outlook in major developed markets and, as a result, suspect that both appetite for “risk” assets generally and corporate earnings growth will deteriorate more than we previously thought.

“Rather than focusing on different geographies, we think it makes more sense to expect a continued divergence in the performance of different stock market sectors and risk factors.”

Rather than focusing on different geographies, we think it makes more sense to expect a continued divergence in the performance of different stock market sectors and risk factors. We believe defensive sectors like consumer staples will generally outperform cyclical ones like consumer discretionary and financials. We also suspect that value stocks will continue to hold up better than growth stocks . That is partly because we see higher bond yields continuing to weigh more heavily on the valuations of growth stocks than those of value stocks, but also because the valuation gap between the growth and value factors in the U.S. still looks unusually high by historical standards, even if it has shrunk a bit this year so far.

“The trend towards tighter monetary policy and weaker growth leaves few economies standing out to us as relative bright spots.”

The trend towards tighter monetary policy and weaker growth leaves few economies standing out to us as relative bright spots. That has left us reluctant to make a call in our portfolios for a significantly better performance from any one country or region. As such, we moved our regional equity positioning to neutral and increased our multi-factor weight, which gives us increased exposure to defensive sectors and companies. We’ve also increased our fixed income weight as we believe most of the rate increases are now priced into bond markets. We believe the combination of these measures will allow our portfolios to best weather the further headwinds ahead.

“With uncertainty being high and sentiment being at the lowest it has been in over 20 years, there has never been a better time to have a plan in place and execute on it.”

Final Thoughts

Investors may be discouraged by our near-term outlook for financial markets and feeling uncertain about their investments - this is only natural. However, we need to recognize that there is a strong correlation between uncertainty and negative emotions, such as stress and anxiety, which have the potential to bias our decisions and that is, in my experience, usually to the detriment of our long-term goals. To manage these emotions, I look for the positive in each situation – the opportunity. This enables me to look through today’s volatility and negative investor sentiment and see the seeds of future returns that we can embrace and capitalize on. I encourage investors to do the same. Timing markets is difficult at best, so developing a systematic plan can eliminate hesitancy, procrastination and rash decision-making. With uncertainty being high and sentiment being at the lowest it has been in over 20 years, there has never been a better time to have a plan in place and execute on it.

Until next time, stay safe and be well.

Corrado Tiralongo

Chief Investment Officer

Counsel Portfolio Services | IPC Private Wealth

Click Here to Read Our Forward-Looking Statements Disclaimer

Investment Planning Counsel