I recalled the parable of the Blind Men and the Elephant this week after a conversation with a colleague. If you aren’t familiar with the parable, you can read it here.

If you know the story well, you know that each blind man described the elephant based on their experience of a single feature of the animal. Though each was right given their narrow experience, none could describe the full picture. Their disagreements were resolved by the wise man who saw the full picture.

The moral of the Blind Men and the Elephant can be related to how you view “expected returns” for your investment portfolio. In short, if you only see things from one perspective, you will miss the big picture.

Events Interfere with Perfectly Good Plans

Returns and risks are what investing is all about and it is a subject that we constantly think about. However, I don’t think I have done a good enough job to articulate what we do, our investment strategy, positioning and market beliefs. My passion for the topic is based on wanting to root out overconfidence in, and for the promotion of humility and pragmatism in investing. So, in this letter, I describe how we think about the world when we manage your money.

Our understanding of the expected rewards and risks that financial markets may offer in the future is central to our investment process. ‘Expected returns’ are how much you make on average overtime on an investment or investment strategy. ‘Risk’, on the other hand, is the possibility that over any time horizon, you don’t get your expected return.

World events have the unfortunate habit of interfering with a perfectly good plan, resulting in expectations for returns not being met.

As such, there is always uncertainty about any expectation. Significant events like the global financial crisis or COVID-19 can make an investor question their financial situation and/or abandon a good portfolio due to short-term uncertainty, or fear when they see their returns trailing expectations. Hence, the need for portfolio insurance (see my last commentary: The Siren’s Song and Investing Without an Air Bag).

So, why estimate future returns? Well, imagine if you made nothing on your equity portfolio in the final decade before your retirement, because you bought them at extremely high prices. We don’t need to look far to know the real possibility of this. A simple review of the 10-year rolling returns of the S&P 500 shows us that since 1925 there were 297 (of 990) 10-year rolling periods in which equity returns after inflation was zero or negative. That’s 30% of all periods! Cliff Asness, the CIO of AQR Investment Management, says it best, “if risk is about surviving the short term, expected return is about whether, after surviving, you think it was worth it!”. So, in estimating future returns, our goal is not just to survive but to thrive.

Overlapping Measures of Expected Returns

So, what do we mean when we say "expected returns"? When we think about returns, we examine them along four dimensions:

- The expected return you get paid for owning one of the broad sets of asset classes: stocks, bonds, cash, etc. We call this return “Beta”.

- The expected return you get through exposure to well-known strategies (known as ‘risk factors’). These include factors such as Value, Momentum, Size (e.g. small cap), Low Volatility, High Profitability and Low Investment. By employing these strategies, you get exposure to a set of risks that is different from what’s described in #1. Hence, the return for carrying these risks is different compared to the risk of just being invested in a market-weighted basket of stocks (i.e: like the TSX or S&P 500). The extra return that accrues to these risk factors is over and above the returns from the universe of all stocks - because there are additional risks or investor behaviours that cause these factors to accrue additional returns over and above a market portfolio of equities.

- The expected return you get from being willing to take the risk of being exposed to economic or other risks. For example, liquidity risk in small cap stocks, or inflation risks in high dividend stocks.

- The expected return we get from pursuing an active strategy. This is what we call “Alpha” – the return we get from an active manager that is over and above returns described in #1, #2 and #3. This expected alpha comes from stock selection, trading and market timing in aggregate and is a much smaller component to overall performance in the long term.

To illustrate the point mathematically, expected returns would look like the following:

Expected return = Rf + β(Rm – Rf) + Risk Factor exposure (b x Value + b x Momentum + b x Size …) + α 1

Rf = the risk-free rate of return (usually represented by treasury bills)

β = the beta value of the investment (a measure of its price sensitivity to market movements)

Rm = returns from the equity market (denoted by a cap-weighted benchmark such as the S&P 500 Index)

α = alpha which is the return from stock selection, trading and market timing

Have I confused you yet? I hope not.

So, all these types of expected returns are connected and overlapping. For instance, the passive ownership of equities exposes you to more risk of poor real economic growth. In contrast, the ownership of a portfolio of bonds increases your exposure to the risk of higher than expected inflation. Case in point, the ongoing experience of COVID–19 and the resulting shock to economic growth resulted in a rapid downturn in equities in Q2 this year. Or, small cap stocks expose you to more liquidity risk relative to large cap stocks due to the potential unavailability of a small cap stock at a good price or to difficulty selling it at a favourable price.

So to recap, there are two ways you can get a positive expected return: the first is taking a risk you get paid for, that would be #1 (market beta) and #2 (factor exposure) or by outsmarting someone else (“alpha”).

So, you can think about then parsing the sources of returns in the following ways: asset classes, factor exposure and alpha. Exposure to any of these three can generate a positive return for the following two reasons: a rational compensation for risk or outsmarting others who are less than rationale.

Now that we have identified the sources of returns, we need to think about a method for estimating returns going forward. There are three ways to go about this:

- You can forecast the future based solely on a theory of how something has done in the past.

- You can forecast the future based solely on your theory on how the world should work without examining the data.

- You can forecast future returns by estimating the cash flows that corporations supply (realized returns can be attributed to corporate fundamentals such as dividends and growth in fundamentals (i.e. earnings, dividends, and book value).

In the long run, the cash flows that corporations supply are the ultimate drivers of stock returns.

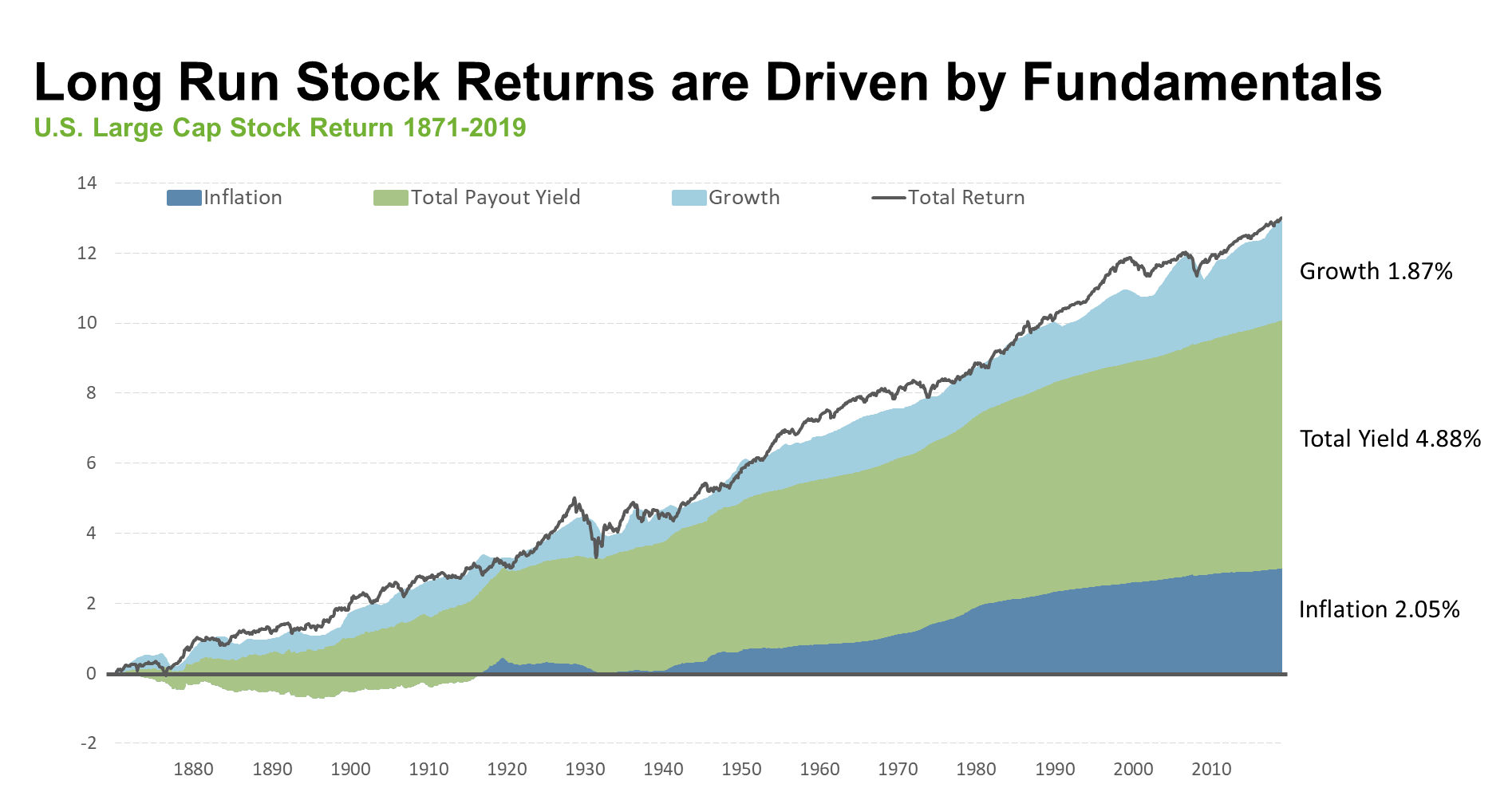

Hence our preference for using method ‘c’ to estimate returns. How that method compares to historical equity returns is illustrated in the chart below. However, markets can and do often get ahead of themselves and, at times, prices will exceed those fundamentals. We can see this represented by the whitespace between the total return line and the mountain chart.

So, as an investor, when you make judgments about the expected returns of various investments, you will need to ensure you aren’t blinded by past performance and consider all of the following:

- Historical average returns

- Financial and behavioural theories

- Forward-looking market indicators

- Discretionary views – in the short run, the stock market is mostly driven by demand, with risk-on/risk-off environments causing over- and under-reaction to the underlying fundamentals (as can be seen by the whitespace between the total return line and the mountain chart in the above chart)

Summary

There are two reasons why you might get paid an expected return, three overlapping ways to divide the different sources of expected returns and three overlapping methods to estimate returns going forward. Each of these provides part of the answer, but not all of it. So all three must be considered for the full picture. I didn’t promise that this would be simple.

Successful investing is a process, one that identifies the structural qualities within a portfolio allocation process to reliably increase the likelihood of success.

It’s about learning from more than 50 years of theoretical and empirical literature and practices to build resilient portfolios in order to avoid (for example) earning zero on your investment portfolio over 10 years because you paid too much. We recognize that as investors, we are impatient. We want to generate high returns over short horizons. Some will succeed, but most will fail. Having a disciplined investment process means that over the medium to long term, we significantly increase the odds of achieving our investment goals.

Stay disciplined with your investment portfolio.

Best wishes,

Corrado Tiralongo

Chief Investment Officer

Counsel Portfolio Services | IPC Private Wealth

Click Here to Read Our Forward-Looking Statements Disclaimer

1 Investors tend to attribute any good past performance to skill (aka “alpha”). We repeatedly get “fooled by randomness” when we equate past performance with skill and underestimate the role of chance. This is true in many of life’s activities. This formula is not only a way to think about expected returns but also a way that my team and I attribute an active manager’s returns to understand how much of it was derived from easily replicable market and risk factors and how much might have been from alpha or luck. For more information on the role of luck, I recommend reading The Success Equation by Michael J. Mauboussin and Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

2 Historical returns are a natural starting point for investment analysis, partly because we are all hardwired to imitate successful actions and to learn from past experiences. Those traits enabled our ancestors to survive and develop, but are harmful in investing. The disclaimer “past performance may not be indicative of future results” isn’t just a legal disclaimer but a warning against following our evolutionary traits.

Investment Planning Counsel