Last week, my 11-year-old son, Leo, presented me with this letter.

What struck me, aside from the fact that it was a well-written argument (at least from my perspective), was his emotional FOMO response. FOMO (the Fear of Missing Out) is real whether you’re a child feeling the social pressures of having the latest phone, or an investor looking at alternatives to your current portfolio.

Why do we have FOMO? Behavioral economics and decision theory help explain some of this. These bodies of study say that common human errors can arise from cognitive shortcuts and biases that affect how we make decisions1. One of these biases, the basis of FOMO, is the Paradox of Choice.

Psychologist, Barry Schwartz, says the more choices we have, the less happy we are with what we choose2. Too many choices can also lead to poor decisions, anxiety, and depressive FOMO feelings.

Schwartz explains it in this TED Talk.

The Paradox of Choice, FOMO and Investing

So why are investors susceptible to FOMO?

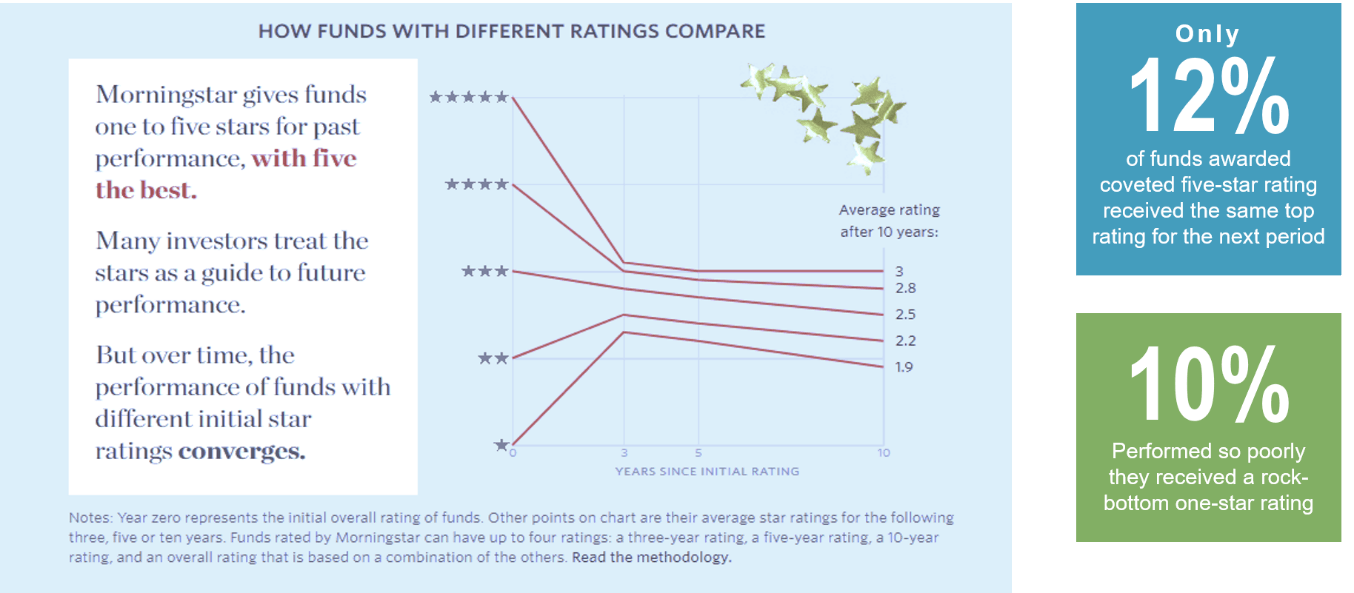

There are some 3,359 unique mutual funds and 969 ETFs in Canada. That’s a lot of choice, and it can – and does – lead to decisions that can be destructive to our long-term objectives. When faced with too many choices, our brains have a way of suppressing ambiguity so that a single interpretation is chosen, without us ever being aware of the ambiguity3. When it comes to investments, that single interpretation is often ‘historical performance’. Unsurprisingly so, as past performance is the most widely available and easily comparable metric. Yet, when used alone, it can also be the most misleading.

Market conditions are cyclical. Styles and sectors move in and out of favour from year to year. As the saying goes, “every dog has its day.” The fact is funds too cycle in and out of favour. Plus, there is a high volume of data and analytical complexity that are not reflected in typical measures used to evaluate funds (such as the Morningstar “star” rating). So, historical performance alone don’t provide enough information on the objectives of a fund or the drivers of past performance for us to make well-informed decisions.

Past Performance is Not a Guarantee of Future Performance

Take, for example, two funds in the same category (e.g. global neutral balanced). The objective for one is to closely match the benchmark or category performance (to reduce investor FOMO). The second fund’s objective is to minimize large losses due to persistent market declines. These different objectives are not reflected in the funds’ names or their category. The subtle differences are discerned only by asking lots of questions.

The key to reducing FOMO and increasing happiness and savings is to understand what’s most important to you as an investor.

Do you want short-term relative performance, or to maximize the probability of meeting your financial goals, while minimizing losses along the way?

My suggestion is to reduce the number of options you consider. Ask lots of questions throughout the selection process. Remember, decisions can be only made with the best information at hand at the time. View limits on the choices you face as liberating not constraining. Focus on outcomes: yours as well as those of your portfolio relative to your financial plan.

When my team and I evaluate investment managers, performance is one of eight metrics. The other seven are qualitative measures (i.e. an investment team’s philosophy, process, people, passion, perspective, purpose and progress). We ask a lot of questions throughout our process to uncover risks and opportunities. This approach helps improve our decision-making process and has enabled us to avoid costly mistakes both in hiring and changing investment managers.

As a parent, and an investment manager

...the lesson here is that there are no ‘right’ answers. We need to be transparent in our choices, stick to our values, and focus on our objectives.

Perfection is not possible whether in parenting or investment management. The best we can hope for is to be right more than 50% of the time and when we are ‘wrong’, that the damage is limited, so that the impact of our successes outweighs that of our mistakes.

Markets and Economics: Investor FOMO May Feel Real Now

Markets rallied nearly 30% through April, but some retail investors would have missed it if they were sitting in cash. For them, FOMO could be real now and they may try to chase returns. The question is, are investors getting ahead of themselves and have valuations become “expensive” again? The following are some statistics that I have been looking at to discern investor expectations versus our own.

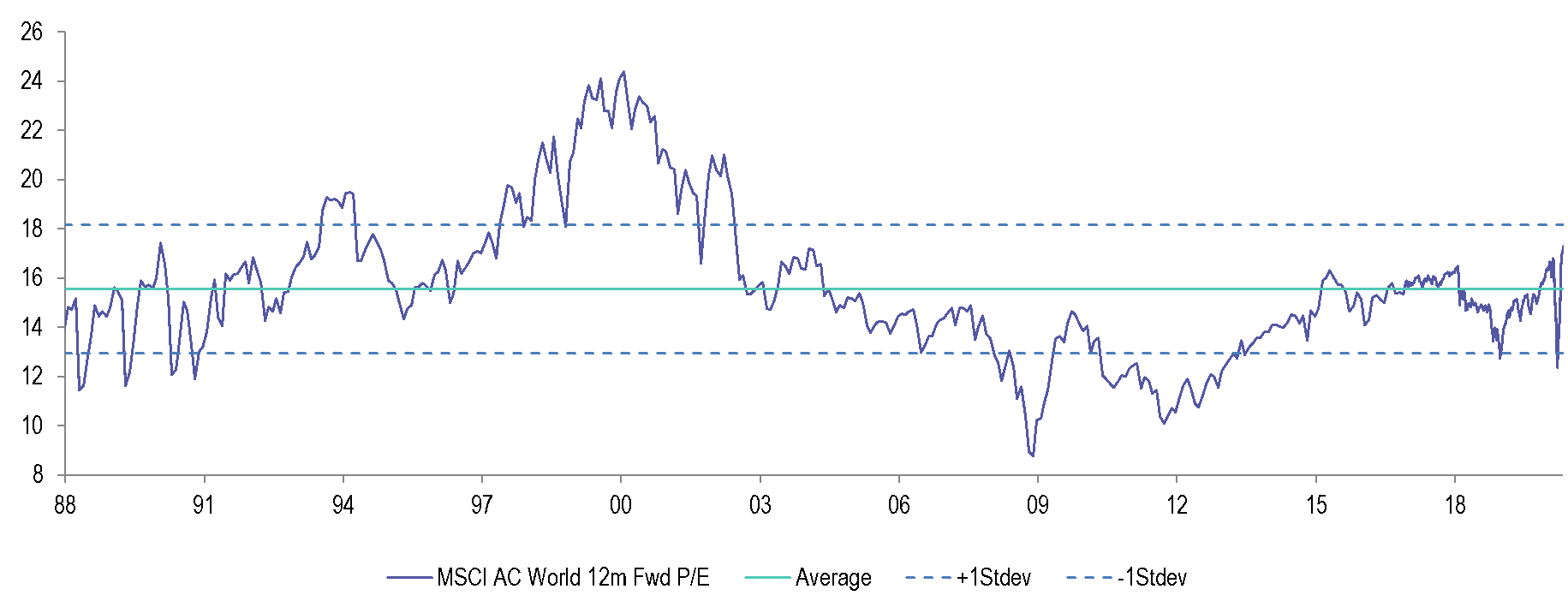

Valuations: The long-run average price to earnings (“P/E”) ratio for global stocks is about 15.5x. As of last Friday, the 12-month forward P/E based on consensus estimates was 17.3x, above its pre-pandemic level. From my perspective, investors are underestimating the damage to earnings this year and next. The consensus projects earnings will contract -14.4% in 2020 and grow 23.5% in 2021. If earnings fall more than estimated, then markets are much more expensive than the 17.3x future earnings implies. One of our investment managers, Irish Life Investment Management, estimates earnings will contract 50% in 2020 and rise 40% in 2021. This implies a 12-month forward P/E of 20.4x, also more than the 17.3x consensus. Regardless of which estimate you use (consensus or Irish Life), the current P/Es are elevated relative to historical the average.

Global Equity 12-Month Forward P/Es are Elevated

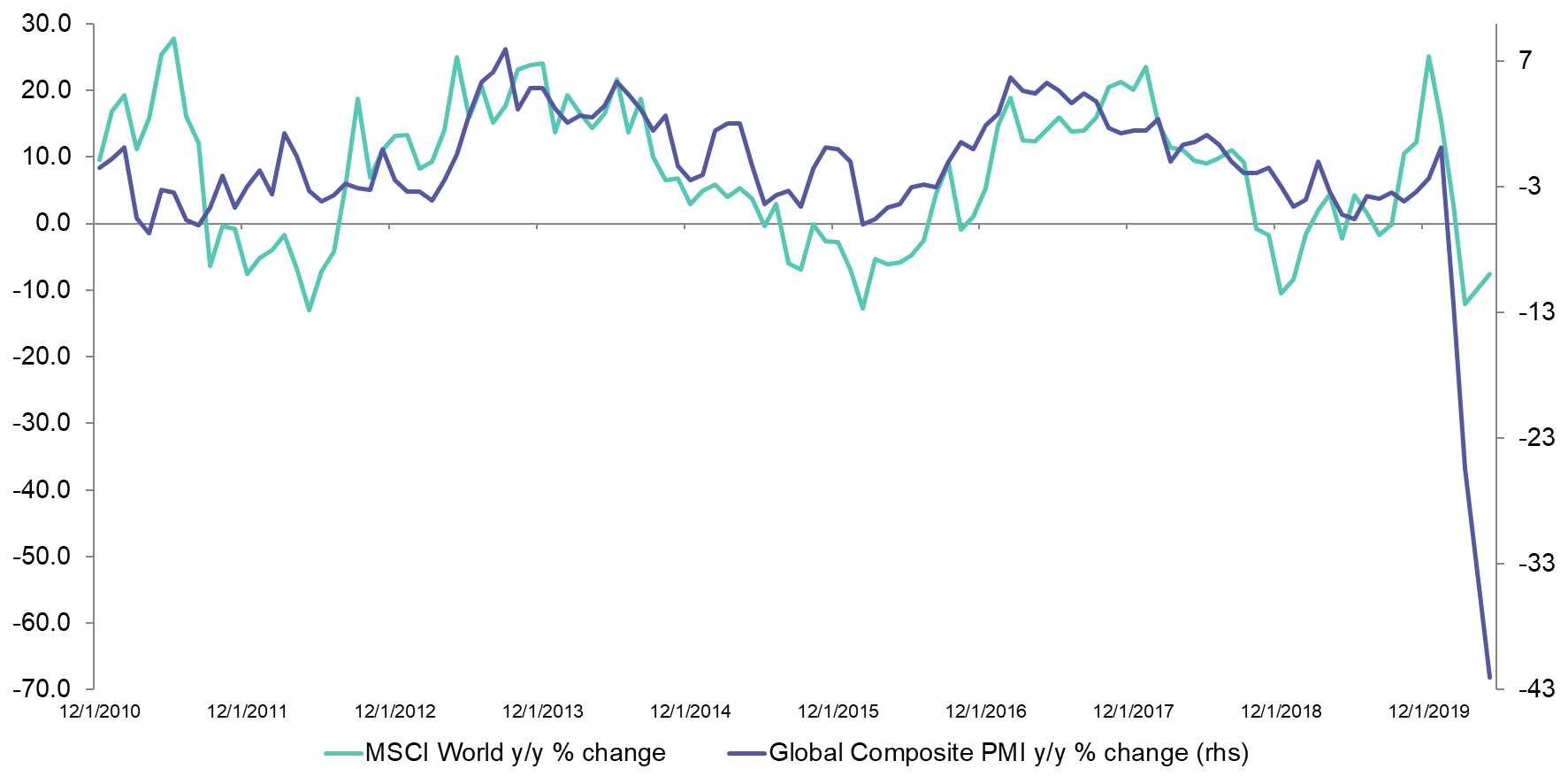

Economic health: The composite Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI), which measures the prevailing direction of economic trends in the manufacturing and service sectors, tells another story. Flash figures for April suggests the composite PMI will have fallen approximately 42% year-over-year. The chart below highlights the divergence in expectations between the current equity market and the economic backdrop – investors are expecting a “V-shaped” recovery but prevailing economic conditions suggest a longer, deeper slowdown.

MSCI World vs. Global Composite PMI

Central bank policies: The rise in equity markets since the March 23 lows are at least partly, if not mostly, due to investor confidence that central banks will continue to intervene and support markets. However, this puts central banks in a quandary, as doing so creates a moral hazard for investors. Central banks don’t want to trigger volatility by signalling that they have no intention to continue to expand monetary policy programs to buying stocks. Instead, they have chosen to be silent, hoping an economic recovery will justify current market valuations. However, a corporate debt default cycle is coming. The question is the scale and duration of damage from defaults.

Though central banks may succeed in blunting the default cycle for now, the debt burden will increase in two to three years – intensifying the pressure to keep rates low.

So, central banks are clearly trapped. Stemming financial turmoil now only loads longer-term costs into the future. Central bank purchases of corporate debt cannot turn bad debt into good debt. One should not make the mistake of substituting monetary policy for credit strength, which will only lead to paying a dear price down the road when downgrades and defaults start.

I could look at many more pieces of data to infer information. However, for the purpose of this letter, these suffice. What we can sum up here are the following:

- Investors are optimistic, based on current valuations, which are expensive

- Businesses are pessimistic, and so the decline in earnings may be more significant

- Central bank policies may have given investors a false sense of security

Another interesting tidbit this past week was the annual Berkshire Hathaway shareholder’s meeting. What came out of that meeting was that Warren Buffett was a very small buyer of stocks in March, when markets were going down, and a seller of stocks in April ($6.5 billion) when markets were going up. He is currently holding almost $125 billion in cash and U.S. treasury bills. Buffett is clearly not in a rush to invest his cash and, given current conditions, it is no wonder.

Markets are driven by fear and greed. Successful investors manage their risk religiously and are fearful when others are greedy. In my mind, this is not the time to be greedy or chase returns. Rather, the best course of action is to remain thoughtful and ensure our portfolios are resilient no matter what the markets throw our way. We are happy to participate and bid our time.

Final Thoughts

I’m not sure that I cured my son’s anxiety of not having the latest phone. Applying logic didn’t work. To be clear, he has my used iPhone 7 (Wi-Fi only), not an “old” phone by any means. I understand that peer pressure and social anxieties aren’t necessarily logical, so I’m taking the long route, having longer conversations as to what is it that a new phone will do for him, how “stuff” won’t make you happy in the long run, and that if your friends only like you for your stuff, then they aren’t really your friends. Complicated conversations to have with an 11-year-old.

With respect to your investments, we continue to focus on protecting against significant and sustained reductions in our clients’ wealth, not on relative short-term performance.

We would be lying if we said that we don’t suffer from FOMO or other cognitive biases. Recognizing that we all have biases, however, means we have a process to mitigate these cognitive mistakes. For my part, I have a checklist that I often reference – one that allows me to question my thinking and identify if I am taking a mental shortcut. Also, it helps that I have a team that isn’t afraid to challenge my thinking. A strong dose of humility is a good thing…!

Until next week, stay safe and be well.

Corrado Tiralongo

Chief Investment Officer

Counsel Portfolio Services | IPC Private Wealth

Click Here to Read Our Forward-Looking Statements Disclaimer

1 Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, 1974

2 Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz, 2004

3 Judgement Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, 1974

Investment Planning Counsel